800 Meter Training Plans

You are welcome to email our coaching staff for a free consultation / discussion about your goals: Rob@Coloradotrackclub.com Otherwise, explore our site and make use of the information and videos.

The 800 meter run is a favorite event for many athletes and fans. As we unpack the complexities of the event throughout this page you will begin to understand why it is such an endearing and difficult event. We have provided enough information for an average person to develop their skills to excel in the 800. Find some reliable sources and continue to study the event, while learning from those who excel at each level (HS, College, and Pro).

Introduction

As discussed on the previous page, once we have an understanding of the athlete’s TALENT and DURABILITY, the key training variables left for us to work on are training VOLUME and training INTENSITY.

Volume and intensity are a result of the amount of TIME and EFFORT the athlete is willing to spend developing their abilities. There are busy professionals who will run 8-10 miles to work in order to get in their base miles, for example. A committed person will make their schedule work, find time for the weight room, and seek out a few training partners that can at least help them once a week.

The Science of the 800 Meters

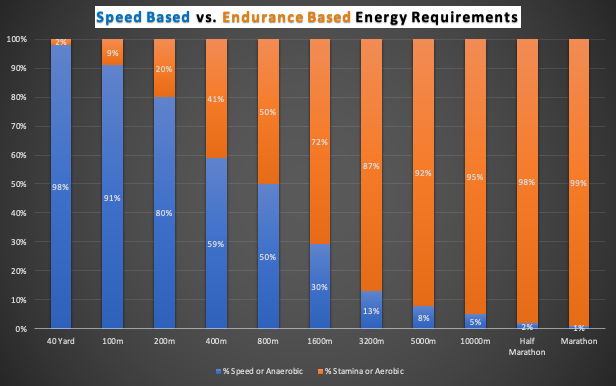

Note: Very smart folks debate these numbers on a regular basis. The concept is more important to me. It is important for us to grasp which energy system contributes to the success of the event we are training for. The 40 Yard Dash in the NFL is a 4+ second, power-based sprint that can be completed WITHOUT breathing. As we prepare for the 800m and up, the aerobic system begins to play a vital role in an athlete’s success. The training must reflect the energy needs of the event. For the 40 Yard and 100m, remember that you need to breathe while in the blocks - oxygen plays a basic role in getting you to the starting line and keeping your organs from failing.

Anaerobic Energy System

The Anaerobic Energy System may be sub-divided into the following systems:

Anaerobic Glycolytic - no oxygen, effective for less than 2 minutes. Important to long sprinters, such as 200, 400, an 800m runners. Plays a role in 100m success as well.

Anaerobic Alactic - no oxygen, effective for about 8 seconds. Explosive sprints, such as the NFL 40-yard dash and a large portion of the 100m sprint.

Scientists and accomplished coaches have quantified / estimated that high achieving 800m runners use the following energy system distribution to excel:

50% aerobic,

44% anaerobic glycolytic, and

6% anaerobic alactic

These are good estimates. Some folks may speculate that it is a 40 / 60 split in either direction. For sure, once a newer coach or athlete thinks they have the 800m figured out there will be an athlete that breaks their mold / predictive model. The 50% - 44% - 6% split seems reasonable to me.

The reality we see with the event is that each energy system is important, but a weakness can be overcome if the athlete is exceptional at one of the energy systems. We had two different athletes in college who did not compete in the 800m - they were both sub 4:00 milers and XC runners. When they did drop down to the 800m they were able to run around 1:48 - the fastest on our talented team. They had exceptional middle endurance capabilities that allowed them to excel in the event. However, there are plenty of 400 / 800 type runners in the NCAA who could run closer to 1:46.5 because of exceptional speed.

The Extras: If you plan on sticking around and progressing in the 800 meter run, you need to develop your understanding about Drills, Core Work, and Weight Training. It can take about two years of consistent work to manage all of these disciplines - I encourage coaches and younger athletes to take the time to teach / learn while in high school. A very small percentage of good college 800m runners do so without having a year-round commitment in the gym.

Types of 800m Runners

Type I Athlete: Does the 800m runner have excellent / respectable 400m or 200m speed?

Type II Athlete: Could the athlete move up to the 1500 or Mile and find success?

Type III Athlete: Is the athlete mediocre at the 400m and 1500m, yet very good at the 800 meters?

Think about the three questions above. If an answer is, “definitely yes,” to any of the questions, then the training approach may be quite different. Many of us love the 800m - precisely because - it is an event that highlights differing abilities and tactics.

The person with exceptional 400m or 200m ability will train to capitalize on his / her speed and to develop just enough endurance / stamina to make it through the race. This person probably has ZERO interest in racing the 1500 meters. This person can win the 800m at the collegiate level.

The person who is also competitive in the 1500 meters will likely capitalize on their middle-distance endurance and work enough to limit the lack of elite sprinting ability. This person can win the 800m at the collegiate level, but you won’t see it as often as the Type I or Type III runner.

The person who is good at both the 400m and the 1500m will strive to mix both abilities to the precise level to maximize performance. This person can win the 800m at the collegiate level.

The athlete that starts out slower in the race has the added risk of navigating lane changes and crowds (tactics), which can be overcome with experience.

The athlete who starts out too fast can wilt before our eyes with only 35 meters to go, getting passed by five people in the last few steps. It is a great event!

High School Runners: Just because you are the fastest 400m, 200m, or 1500m runner at your school does not mean you are “fast.” Look at the rankings on Milesplit or TFRRS.org to see your ranking in the 400 or 1500. You may be a good athlete at a slow school. For HS male runners who are fastest at their school, but run an 800m in about 2:05 (or slower), look at the TFRRS.Org rankings for female college athletes in the 400m and 1500m to see where you would rank. This may help you to determine your actual strengths.

Explore Your Weakness: Make sure you don’t miscalculate your strengths or weaknesses without committing about two full seasons (6 months each) of working on your abilities. Many HS or community runners falsely lean toward declaring they are a sprinter or endurance runner.

In HS, many sprinters have no desire to do the demanding endurance work that they see the distance team doing. Since they only lose by 1-3 seconds in the 200m, they perceive they are good… at sprints, versus losing by 60-90 seconds in the Mile to a teammate.

Likewise, some folks have very little development in coordination-based activities and prefer to just jog because it feels more natural / comfortable. With some drills and footwork this athlete may improve significantly in sprinting and endurance ability.

Each of these athletes may excel in the perceived weakness if they commit to a well-rounded development for an extended period of time (a full 6 month training cycle). In summary, I am slow to trust an inexperienced runner until I can spend about a year observing a few specified workouts to build up their perceived weakness.

Volume Recommendations

To me, VOLUME is the amount of mileage, or time running, that is needed to make most runners highly successful in the event. There are always exceptions, but my recommendations are based on my observations of thousands of runners, not the exception. I include warm-up routines as mileage.

Type I 800m Runner (Speed Based) Mileage / Volume

High School: 18-30 miles per week, 32-46 weeks of the year.

This athlete is likely playing another sport that basically reaches similar mileage during practice and games (he / she is not running another 18 miles per week outside of practice). An athletic basketball small forward or guard, or a high speed wide receiver come to mind.

This athlete likely has some experience or aptitude in the weight room as well, possibly from the other sports.

A new HS runner should allow several months of work to get to these volumes. If the athlete has a significant athletic background in other sports, he / she may be able to get to these volumes in their 1st season. Watch for signs of overuse injuries.

College: 28-45 miles per week, 38-47 weeks of the year.

This athlete is likely a 1 sport competitor now and will generally have to put more focus into track to stay competitive.

The 1:56 / 2:13 (boys / girls) times in high school are no longer adequate to excel at the next level.

The weight room is likely very important to this athlete.

Type II 800m Runner (Mid-Endurance Based) Mileage / Volume

High School: 25-45 miles per week, 34-46 weeks per year.

This athlete may be running well in cross country, basketball, or soccer - accumulating the aerobic base / mileage needed to build a powerful aerobic approach to the 800m.

The weight room may be used, but is not a focal point - the athlete makes up for a lack of weight training with the extra mileage.

A new HS runner should allow at least two seasons of work to get to these volumes. If the athlete has a significant athletic background in other sports, he / she may be able to get to these volumes in their 1st season, but 45 miles can be a lot for some younger people to handle. Watch for signs of overuse injuries.

College: 33-60 miles per week, 37-47 weeks per year.

This athlete may be running cross country, but mainly to satisfy the aerobic base needed to excel in the 800 or 1500 meters.

The weight room is more of a factor than when the athlete was in HS.

Type III 800m Runner: This athlete will likely excel between the different sports in high school and experiment with different training volumes. In college, the athlete does not fit in perfectly with the speed or endurance folks, but he / she will excel in the 800m and find their niche on the team.

Intensity Types

To me, INTENSITY refers to the types of paces an athlete runs during their training week, the percentage of volume run at those different paces, and the amount of recovery / easy running provided. I’ll also refer to this idea as Training Density (my term).

Types of Paces: Athletes and coaches do not need to refer to these paces by any proper name, but the vast majority of competitors experiment and figure out ways to become fit by working with these speeds:

Maximum Velocity - 100m Race Pace: The athlete’s top speed, as measured around the 40-55m mark of a 100 meter sprint. We often measure it with a Flying 30 Sprint. We test and care about Maximum Velocity because it is a measurement of running explosiveness, mobility, and fitness. It is relatively important to the Type II 800m runner as well, even though he / she may not be able to hang with the sprinters. Worth considering, we (CTC) care about Max Velocity for all 5000m runners and below.

200m - 300m Race Paces: These paces are rarely used in an 800m race, even for the Type I folks, because they will lock the legs up well before the finish. These paces are used in training to build speed endurance. You may see them used in 120m - 180m repeats with barely adequate rest, or a 3x300 @ 99% effort with 15 min rest between each. Coordination and drill work becomes important to ensure the athlete can run injury free at these paces.

400m - 500m Race Paces: These paces are used early on in a hot 800 to get in front of the pack / out of traffic. Used in training in workouts such as 250m Sprint-Float-Sprint repeats. It is a difficult pace to train at because it can burn the athlete up quickly.

800m - 1600m Race Paces: Used in training for 200m repeats or similar work. 800m specialists may work these 1600m pace repeats in the off season with an extended rest, such as a weekly 8-12 x 200m at Mile pace, with a 2:30 rest. As the season approaches, the rest period may be cut down weekly and the speed may get closer to 800m or 1200m race pace.

Read Winning Running (Coe), Athletics (Wells Cerutty), and Better Training for Distance Runners (Martin / Coe) to broaden your understanding of strength and speed development at the Olympic level.

Strides: Strides are fast runs at short distances that many athletes do multiple times per week - usually during warm-ups or at the end of a workout. Strides are helpful to support the development of neuromuscular coordination. Strides also build leg strength over months and years. Here is how we assign and define strides.

Vo2Max Pace: Measurement / reflection of Aerobic Power. It is a range of work that most coaches dial in between an 8-15 minute race pace ability. It may be difficult to establish an accurate 10 minute race pace ability for a Type I 800m runner, for example. This person may detest / fear the 3200m time trial. The Type II 800m runner, however, will find great benefit from these workouts. Monitor the Type I runner during these workouts - they may not recover quickly and jeopardize upcoming training days. We have three EXCELLENT ARTICLES that explain VO2Max concepts in detail. Start with VO2Max #1, then read #2, then read #3.

Lactate Threshold: Also called Anaerobic Threshold. Also called a Tempo Run. This finicky pace represents the exact tipping point on a run where the body is just able to keep up metabolically. The pace is about 45-60 minute race pace (15K-20K race pace, maybe). The body is slowly breaking down during the run, but is able to remove the waste products just enough to keep up the pace. We have three EXCELLENT ARTICLES that address workouts at this pace. Start with Lactate Threshold #1, then read #2, then read #3.

Read Daniels’ Running Formula (Daniels) and Road to the Top (Vigil) to expand your understanding of aerobic development at an Olympic level.

Moderate - Harder Aerobic Runs: These paces are all slower than Lactate Threshold Pace. The paces are not difficult… until you try to sustain them for 50-120 minutes. The weekly Long Run may fall into this category. An extra 4 miles at the end of a workout may fit the description as well.

Aerobic Threshold Run: This is a slower / easy pace where the heart rate settles around 140-145 BPM. It is a basic aerobic development run that an athlete could do for “days” aerobically, if only the muscles could function that long and the glucose and fatty energy sources remained effective. This run proves beneficial for most athletes to raise aerobic system / endurance attributes. The runs should be a minimum of about 45 minutes, but an occasional run up to 90 minutes is beneficial for the 800m runner.

Read Highly Intelligent Training (Livingstone), No Bugles, No Drums (Snell), or Running to the Top (Lydiard) to expand your understanding of aerobic development at an Olympic level.

Weekly Schedule

An athlete has a schedule that helps them to add in, and spread out, the different intensities each week - including weight room, strides, drills, and core work. We often use a 14 day schedule. Here is what a sample schedule may look like.

Measurement of Effort

We can measure intensity by the pace of the run, heartbeats per minute, lactic acid present in the blood, or rated / relative perceived effort.

The methods are not exact and not applicable to all runners. This is likely why some runners excel when they change training programs or coaches.

Pace (Race Paces) Intensity: Discussed above.

Heartbeats per Minute (BPM): Explore the concepts here.

“Lactic Acid” Present in Blood (not a completely accurate term): Explore the concepts here.

Rated Perceived Exertion (Some call it Relative Perceived Exertion): Explore the concepts here.

Approach to Training

Training Seasons: I am assuming 2 x 6 months training periods per year. I am okay if one block gets shortened to 16 weeks.

This approach does not work for colleges, where 800m runners compete for Indoor League Championships in late February, and then for Outdoor Leagues in early May. - about 10 weeks later.

On the Pro / Semi-Pro side, we have athletes competing in different countries, Indoor and Outdoor. We can settle into a 6-month training block, which helps with a predictable annual build-up or increase in volume.

This is merely a sample schedule that may help an uncoached runner, or a new coach, to consider types of workouts at different points of the season.

Here is the macro view of a 6-month (or 26 weeks) training period

Supplements & Nutrition: Understand the USADA / WADA requirements – study all parts of the website if you are an inspiring pro. There is a helpful information on the website that addresses nutrition as well. I recommend the book, Racing Weight (Fitzgerald) as a starting point – good book about body composition and nutrition.

Weeks 1-2: Athlete off. May only run 2-3 times per week with some cross training. Visit family and friends, vacation, etc..

Weeks 3-9: 7 weeks of general fitness and mileage. Prepare the body and nervous system for the challenging work in later weeks.

Type I 800m runners will have 3 EASY speed sessions per week (out of 12-13 sessions per week). These are lower volume and / or higher rest sessions. The athlete should not leave the session miserable. RPE of 5-7. You are not looking for massive acid build-up during this part of the season.

Type II 800m runners will have 2 speed sessions per week (out of 12-13 sessions per week).

Don’t forget that Strides are still happening regularly.

Both types do Max Velocity work weekly as one of the Speed sessions. This may look like 6 x 30m fly, 2 x 50m fly, 1 x 60m fly. Full speed.

Another speed session may be 12 x 200 w/ 2:00 rest. Pace may be 32 / 35 (Men / Women) during these weeks, but will progressively get faster as the competitive season approaches. This would be for 1:52 / 2:08 runners.

Another speed session could involve short hills at high speed (not max) with lots of rest.

Weekly Anaerobic Threshold run of 20 minutes minimum.

Give a little attention to some VO2 pace work. Low volume. RPE 5.

Weekly longer, easy run. I prefer a moderately challenging long run, but it can mess some 800m runners up. There are some GREAT 800m runners who have very little use or emphasis for traditional long runs. There are also former World Record holders who added a competitive marathon to their training regimen in season! I think he ran a 2:43, which included sitting down for a while...

Significant cross-training and weights: high volumes of sets and reps and lower weights.

Add some bodyweight exercises at the end of workouts, about 3 times per week. These will be done for all 26 weeks.

Quality weekly sessions dedicated to drills and technique. Become familiar with the importance of neuromuscular coordination development and plan it into your program all year. Type I and Type III 800m runners will excel with a commitment to weight training and Drill work. Most Type II runners will need it as well, but you will find a few exceptions - people who dominate with massive aerobic power.

Weeks 8-21: Moderate and heavy VO2 pace (5K and 3K) type work

Continue with much of the previous work and progress toward the more challenging speed sessions. If you started your 200s in early season as 12 x 200 @ 32 / 35, you should be closer to 12 x 200 @ 29 / 32 by Week 10. Have a plan and keep progressing slowly. Increase rest if the athlete is miserable.

Max Velocity Days continue

This is the aerobic development window where heavier VO2 pace work is going to be most valuable.

This VO2 work will drop off over the last 6 weeks of the season, but it should be a focus now.

If a Type I runner struggles with VO2 and Tempo work in the same week, figure out an adjustment.

The Type II runner will likely benefit during this period.

Start at 5K pace and gradually get down to 3K pace work by Week 19.

8 x 800s, 6 x 1000s are examples with 1:1 rest.

The Type I runner may need 1-2 less reps… or shorten the distance of the last 3 reps. We are working on a weakness, not trying to demoralize the runner.

Hill sessions can get a longer and slower during this period. 6 x 300 or 5 x 400 meter hills at 93% effort. Medium rest, for example. The athlete should be winded aerobically, but not destroyed. The legs should have the muscles to handle the work - tired, but not destroyed.

Weight training is intense and important during this phase. Lower volume of sets and reps and high weights. Allow recovery time from weight training.

Add a few over-distance races. 3000m, 1500m, Mile, etc… Run a 5000 around Week 15, maybe not for time, but very hard. These are low mental stress races for the athlete. No expectations - just work hard.

Make sure easy days are EASY!

Weeks 17-19: Pre-meets, time trials, introduction to heavy anaerobic speed work.

You will begin to do some stuff like 3 x 300 very fast. With 10-15 minute breaks. Some nastier hill sessions: 8 x 400 at 93%, for example.

Keep up the VO2 and Tempo work.

500, 400, 300, 200 @ 800m race pace with plenty of rest between each. Begin to master your pace without destroying yourself - technical proficiency.

Make sure easy days are EASY!

Weeks 10-17 are likely some of the highest volumes of the season. The endurance phenom (Type II) will likely hold the high mileage closer to Week 17. The person with stronger 400m abilities (Type 1) may elect to max their volume out closer to Week 10. After this period, volumes are going down slightly and intensities are continuing to rise.

Weeks 20-26: 7 Weeks of Championship / Tour type meets. Trying to advance or qualify. Heavy anaerobic workouts and racing.

Now you are gradually backing down from the VO2 work and Tempo work. The Type II runner may hang on to those workouts for about 10-14 days longer than the Type I runner. Both athletes may keep doing them, but the total volume will not be nearly as demanding as it was. The Type I runner likely knows if the Tempo or VO2 work is best for them - hang onto the workout of choice and cut the other more quickly.

This is not the time for unhappiness. Back off trying to develop your weakness at this point. It’s time to sharpen your strengths and prepare for the pain of racing.

You are getting after workouts like the Metric Mile Test for Sprinters: 5 x 300 on the track with 15 minute recovery, add all your times together for your Sprinter’s Mile Time.

600m PR attempt in Week 23 may be good.

3 x 500 @ 800m race pace, with 8 minute rest, would be a very tough workout. 1 x 600m at 800m race pace, then add on some 200s. Research Special Endurance workouts and come up with a plan.

Basically, you are getting some tough long sprint workouts to get the athlete used to the pain of the 800m. It is also important to work on / review tactical situations - help the runner to identify the situations where getting boxed in occur, when to ride it out, and when to force your way out.

Plenty of rest. Starting in Week 21-22, weight room work will shift towards maintenance and not growth. Save the energy for the hard track workouts.

Make sure easy days are EASY and hard days are HARD. You can get about 3 HARD days per week, including race days. On race day, add some more medium-quality 150s, 200s, or 300s after your race.

The Volume (discussed in the middle of this web page) and the Intensities (discussed on the bottom half) are merely EXAMPLES to help uncoached athletes or new coaches to consider training and workout ideas. We make adjustments weekly and our primary goal is to make sure the athlete is confident mentally to race. That confidence comes through challenging workouts and prep races.